How this property downturn is different from the big one in 1989

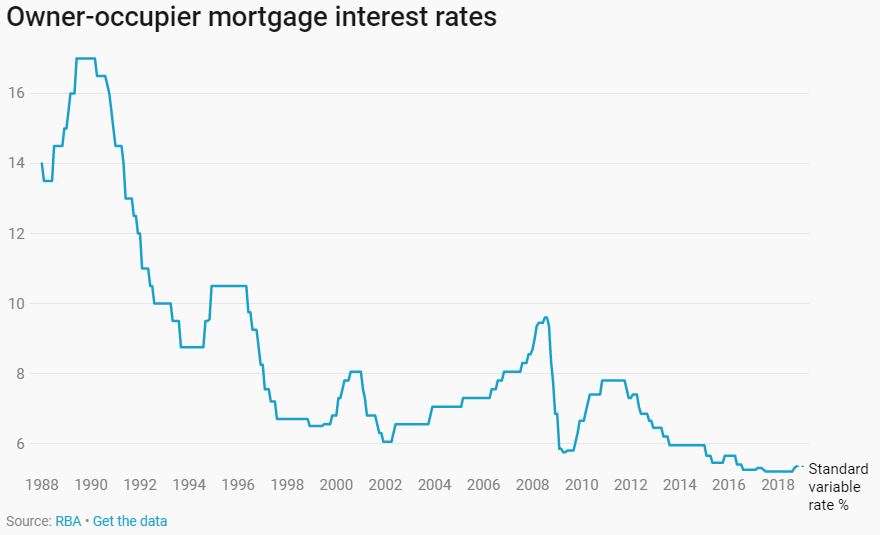

The last time Sydney property prices fell this much, mortgage rates were around 17 per cent, unemployment was 6 per cent (on its way to 11) and Australia was heading into the recession we had to have.

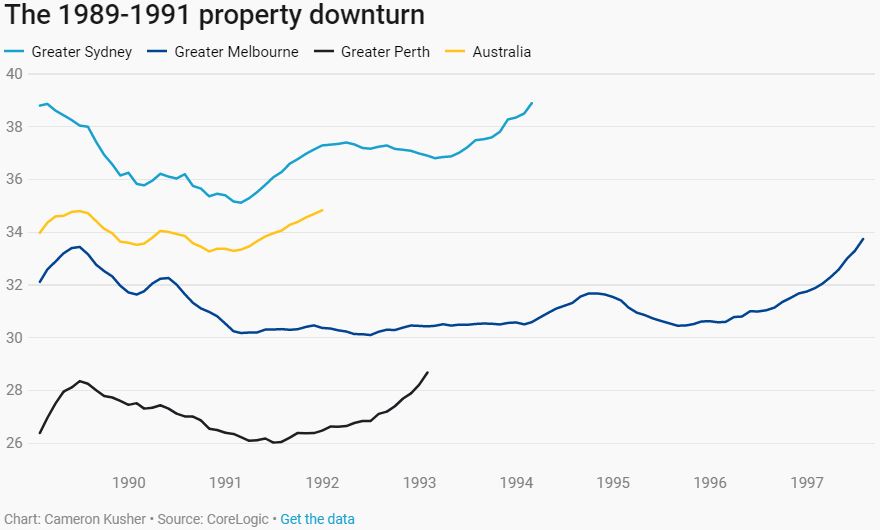

This is what that 1989 downturn looked like — short and sharp in Sydney and Perth, and lingering in Melbourne (which didn’t get back to its late-80s peak until 1997).

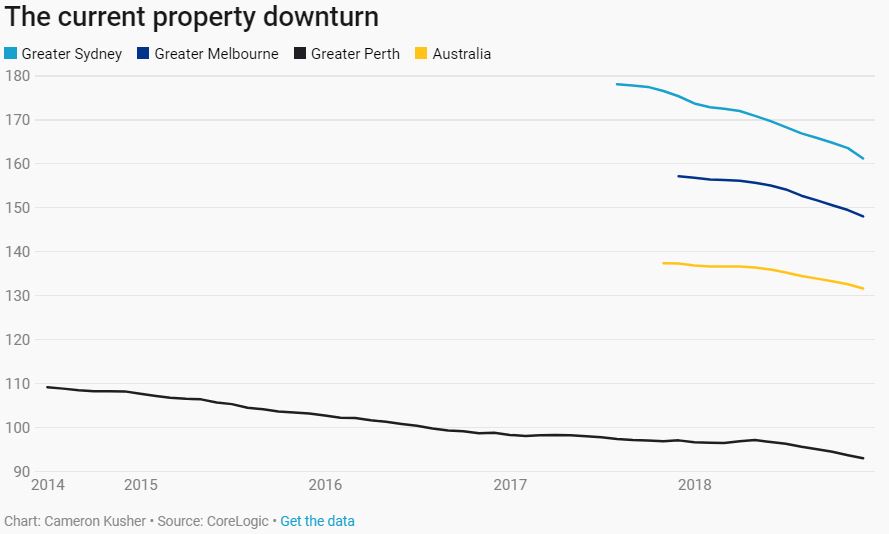

What a contrast to the current real estate downturn, where new borrowers can get mortgage rates under 4 per cent, unemployment is at 5 per cent and has been falling for the past few years, and the latest official figures out this week are expected to show the economy growing above average at 3.3 per cent.

Despite these near-boom conditions, property prices are falling fast in the south-east capitals, while Perth’s stubborn decline simply refuses to end.

This, of course, raises the question of why Sydney and Melbourne are recording big price falls while their economies are chugging along perfectly well.

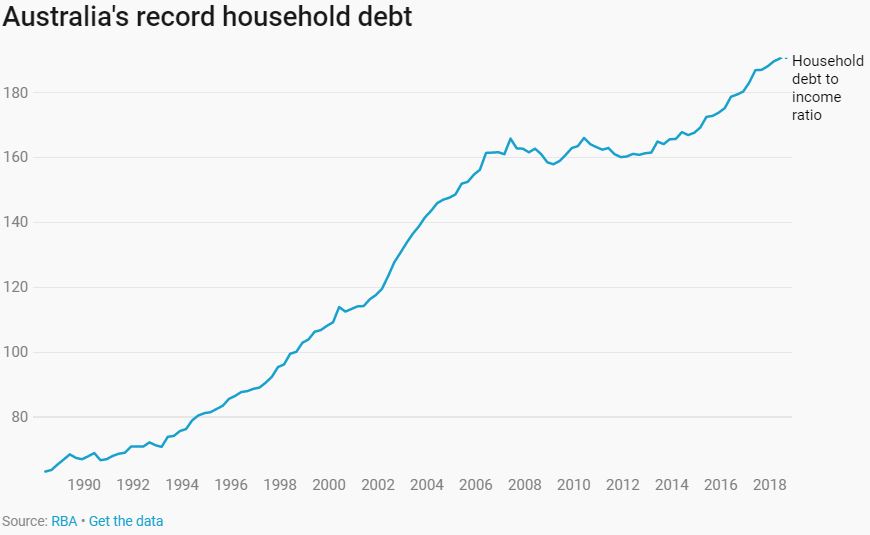

There isn’t a single answer, but one factor stands out and it is same trigger that caused the late-80s correction — mortgage debt. But for very different reasons.

In 2018 buyers can’t get the money

Despite what many economists argue, the single most important factor that determines home prices is credit availability.

It’s intuitive — very few people can buy their first home without mortgage debt, so how much you can borrow will determine how much you can pay. Most investors also rely heavily on debt for their purchases.

At least for owner-occupiers, many people in very crowded markets (Sydney and Melbourne) will borrow close to as much money as they can to buy the best home in the best location they can afford.

How much you can borrow depends on how much banks are willing and able to lend you at a given point in time, given your income and living expenses.

The most immediate trigger for the current housing downturn is that those lending standards have tightened, especially the assessment of living expenses.

For many years Australian banks kept expanding the amount of credit that they’ll provide to prospective home buyers and property investors.

Even the global financial crisis barely slowed the lending binge, as the Federal Government’s bank guarantee kept credit flowing and its first home buyer boost scheme stoked demand.

In the process, mortgage lending standards eroded so far that most banks used low-ball expenses estimates to bump up the amount they could lend, along with evidence of widespread fraud and deception about borrowers’ income and other debts.

But the taps have finally been turned down — first by the banking regulator (with a particular focus on investors) and then by ASIC’s belated enforcement of responsible lending laws and the banking royal commission’s strict interpretation of how loan applicants should be assessed.

Housing credit is still growing, but at the slowest monthly pace since 1984 and the weakest annual pace since 2013, and it is still decelerating.

The equation is simple — if banks now lend buyers 20 per cent less than they were before, that means those buyers will have about that much less to spend on their purchase.

There may be some buyers who have access to savings or existing housing equity that won’t be affected quite as much, but clearly home prices will fall significantly.

The largest falls will be in the most expensive markets where people have to borrow more relative to their income — i.e. Sydney and Melbourne — and this is exactly what we’re seeing.

In 1989 people couldn’t afford the money

Interest rates were in the double-digits throughout the 1980s, because inflation was also very high (mostly between 6-10 per cent in the second half of the 80s).

However, things took a nasty turn when the average standard variable mortgage rate jumped from 13.5 per cent in June 1988 to 17 per cent in June 1989.

This 25 per cent rise in interest rates in just a year had two significant effects.

First, it put many borrowers in severe financial difficulty, no doubt causing some to sell, either by choice or because they had defaulted on their loan.

Second, potential borrowers also would’ve been assessed for loans at the higher interest rates, meaning their borrowing capacity was reduced — a similar effect to what tighter lending standards are having now.

As in the current environment, smaller loans inevitably mean smaller purchase prices.

Regulated credit crunch better than rate spike

Even though Sydney property prices are about to surpass their late 1980s decline, and Melbourne looks set to follow in the new year, the principal trigger for this housing correction seems less dangerous.

Rather than pushing people into default with high interest rates — as the RBA did in the late 1980s — APRA, ASIC and the royal commission are simply forcing banks to lend more responsibly.

This has reduced property prices but will also, if sustained into the future, cap household debt levels and gradually reduce risks in the financial system and economy.

While interest rates remain this low, even most of those who shouldn’t have been granted loans can probably keep meeting their minimum repayments and avoid a forced sale into the falling market.

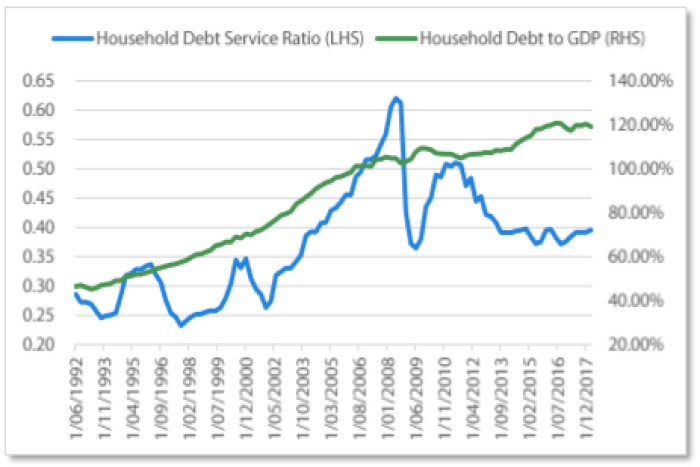

Chris Rands, a portfolio manager at funds manager Nikko AM, says debt servicing levels are around long term averages meaning “the ability to repay that debt is by no means stretched”.

If the current housing downturn is mainly being caused by the tighter lending standards implemented in 2018, those lending standards are already in place, unlikely to be tightened much further, and prices should be nearing a trough.

Already, Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe warned in a recent speech that Australia needs banks prepared to make loans in the expectation that some borrowers will not be able to repay them.

“If they become afraid to lend simply because of the consequences of making a loan that goes bad, our economy will suffer. So a balance needs to be struck here.”

Tighter lending standards not the only issue

However, it is not solely tighter lending standards that have caused the current decline.

The bank regulator APRA’s efforts to rein in property investment, though now relaxed, have reduced a key source of demand in the market.

It’s a source of demand unlikely to rebound strongly soon, given that Labor is highly likely to be elected and implement promised restrictions to negative gearing and a reduction of the capital gains tax discount.

Foreign investors have also pulled back from the market, in part because of tougher enforcement of investment rules and increased state taxes on purchases by overseas buyers.

At the same time, housing supply has surged, especially of apartments in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

Most analysts denied there was a housing oversupply until the last year or so, but the majority now appear to have changed their mind.

While credit availability is the key determinant of property prices for more desirable homes in good locations, this increased supply and reduced demand should start pulling down prices at the lower end as the buyers who remain have far more choice and less competition.

This is where population policy is a key uncertainty.

If Australia dramatically cuts back on its combined permanent and temporary migration intake then there will be fewer people to soak up this excess supply, meaning any adjustment will take longer.

But, with developers already canning new projects, if population growth remains around current high levels the apartment glut may not last too long.

Interest-only reset the biggest domestic risk

Perhaps the biggest risk, though, is the hundreds of thousands of interest-only mortgages due to reset to principal and interest repayments over the next few years.

At the peak of the recent property boom, interest-only loans accounted for around 40 per cent of new mortgages being issued, and even more in markets like Sydney.

These loans became so prevalent that bank regulator APRA introduced a cap, so that no more than 30 per cent of any bank’s new lending could be interest-only.

Most of these loans reset to principal and interest after five years, meaning the big roll-over started in 2018 and will run until 2022.

The increase in repayments on the switch to principal and interest can be 35 per cent or more — a much bigger shock than those 17 per cent interest rates were back in 1989.

Banks have already raised rates on interest-only loans to encourage borrowers to switch to principal and interest ahead of the interest-only period expiring, and tens of thousands have.

However, the risk remains that those who haven’t are those who can’t afford the switch to principal and interest.

If that is the case then there could be a wave of forced sales to add to the regular sales and investors who have already bailed out.

While sentiment around whether now is a good time to buy has improved in Sydney, there probably isn’t yet the pent up demand with finance available to soak up even more sales without further price falls.

Source: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-12-05/two-very-different-housing-market-downturns/10580614